After reading a variety of sources outlining the push and pull between those in academia doing “serious humanities” and those doing “serious digital analysis,” one of our first assignments in the program was to provide a definition of digital public humanities (DPH). I likened DPH to an estuary where the fresh and ocean water comingle to create a distinct ecosystem, one that is known for being one of the great nurseries of the natural world. Having worked on this internship for almost a year, the estuary analogy remains appropriate for my experience working at the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, and not simply because the Anacostia River, for which the neighborhood and museum are named is, in fact, an estuary.

Digital public humanities often blurs the lines for

traditional methods of academic output that can be unfamiliar for those working

in more classical modes of research and presentation. However, it is a unique space that nurtures

not only new methods of presentation, but also new tools made widely available

to a growing body of users.

Initially, the desire of the museum staff was to create some lesson plans to go along with the exhibit that could be published on the museum web site. When I first mentioned creating a digital exhibit both to serve as an educational platform and to preserve public access to A Right to the City, museum staff were concerned about the feasibility of creating a digital project while maintaining the high academic standards of the exhibit in a timely manner.

In the introductory course, one of our final assignments was to consider how Digital Harlem was not meant to be a construct to present a conclusion akin to a dissertation but rather to be a tool to invite historical inquiry in a way that would not be possible using traditional methods. Clearly, getting ARTTC into digital format and out to the public would require using the right tool, and I began to consider using StoryMaps.

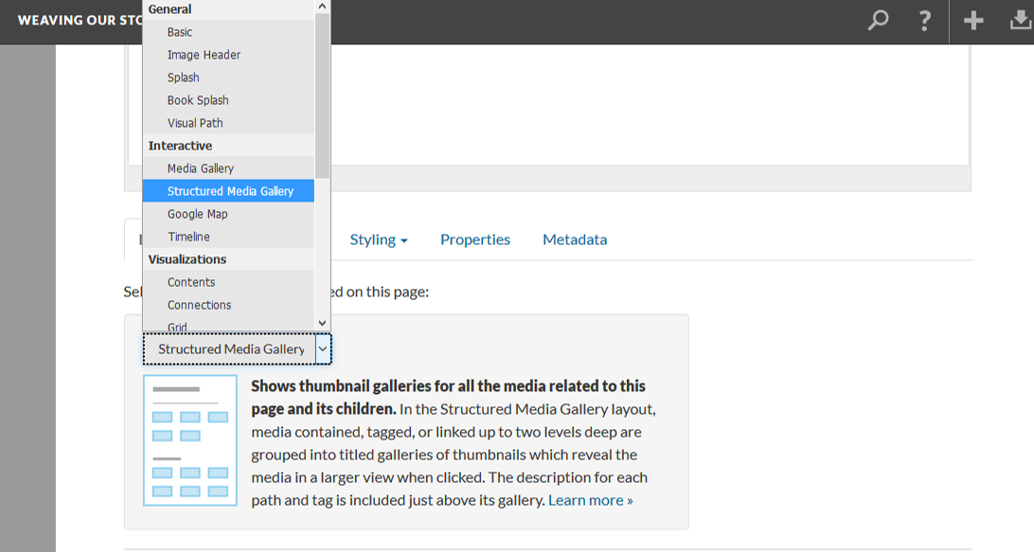

Though mapping is foundational to both Digital Harlem and StoryMaps, each uses that computational power for a different purpose – making them very different tools. StoryMaps seemed like the right presentation tool to take ARTTC to the digital public, to enhance the exhibit content through its mapping capabilities and to deliver the project in a way that is manageable to museum and SI staff.

However, I did have some difficulties with StoryMaps as an academic presentation tool because it is limited in its ability to provide captions across all content blocks, something critical in designing a museum exhibit. I created a work-around for it in my project; however, StoryMaps designers should build this functionality as a more intuitive feature to meet the needs of academia, especially for smaller museums like ACM that have limited resources in developing digital content. This highlights the push and pull between the various constituencies in DPH and the need for greater communication to address these issues. (Update as of June 2020: The StoryMaps team was and continues to be responsive to feedback, and these issues have been resolved. The development team is responsive to feedback as new features and capabilities are unrolled.)

Greater communication is a critical need in the DPH community. The tools are out there, but many operating in more traditional methods are unaware of their existence. For example, the concept of Digital Harlem might be of use to the work around urban history in Washington DC to reach new conclusions or to visualize DC history in a new way.

Looking ahead to the promise of digital public humanities, it

is increasingly important to promote the availability of easy-to-use yet

powerful tools like StoryMaps in

order to place them into the hands of academicians. “Doing digital humanities”

means making the tools more accessible to all – to museum professionals, to scientists

(both computer and natural), to curriculum specialists, to educators and to

students who have knowledge and ideas to share and information to gather. It is

equally important to begin to talk about digital public humanities more

broadly, inside academia and out, so that the public understands new possibilities

of visualizing and presenting information, like the Digital Harlem project, in order to

better engage and to better understand the communities and the world around us.