Working in Scalar

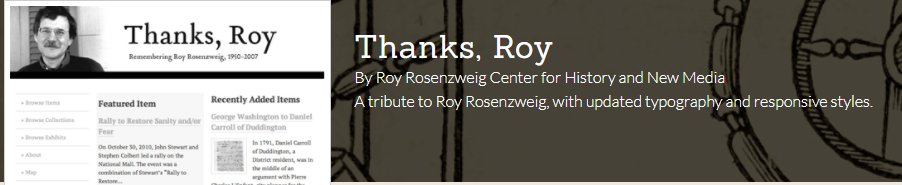

This week I have had the opportunity to really dig in and figure out Scalar, an open source digital publishing platform developed by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture. Dr. Whisnant encouraged me to not limit my vision for the project by what was possible in any particular tool. Though it is a drawback that each book is published within Scalar’s platform and not through an independent install on a URL of my choosing, I am happy to report that Scalar seems to be the right tool for the vision.

Once one registers for a Scalar account, it is possible to create multiple books on Scalar’s platform. One can begin a book by uploading content from local files. Scalar is also able to import digital files from partner archives such as the Getty Library and Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as from affiliated Omeka sites, SoundCloud, YouTube and Vimeo. Each imported item receives its own page with accompanying Metadata intact. Each page may be tagged (non-linear) by term(s), or it can be designated as a path (linear).

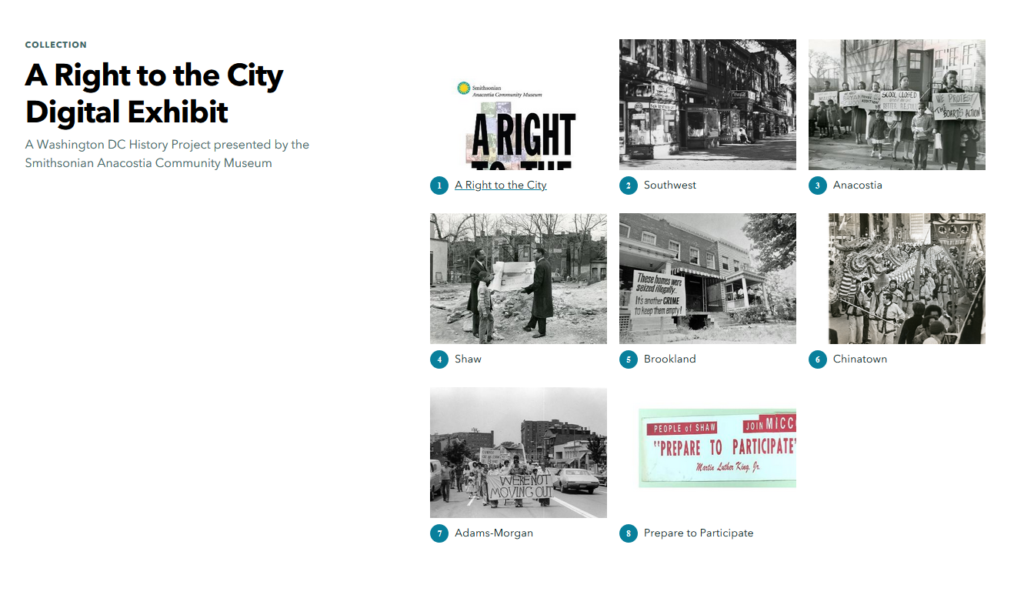

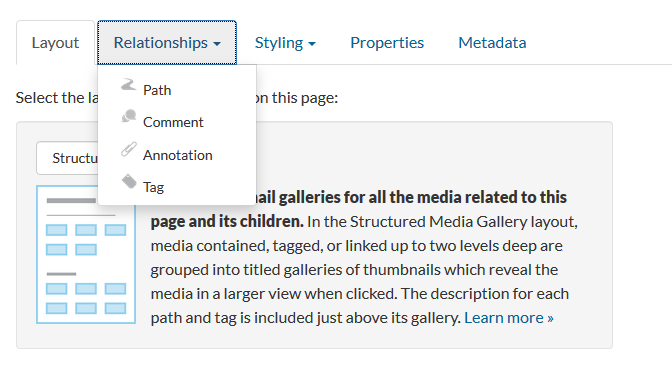

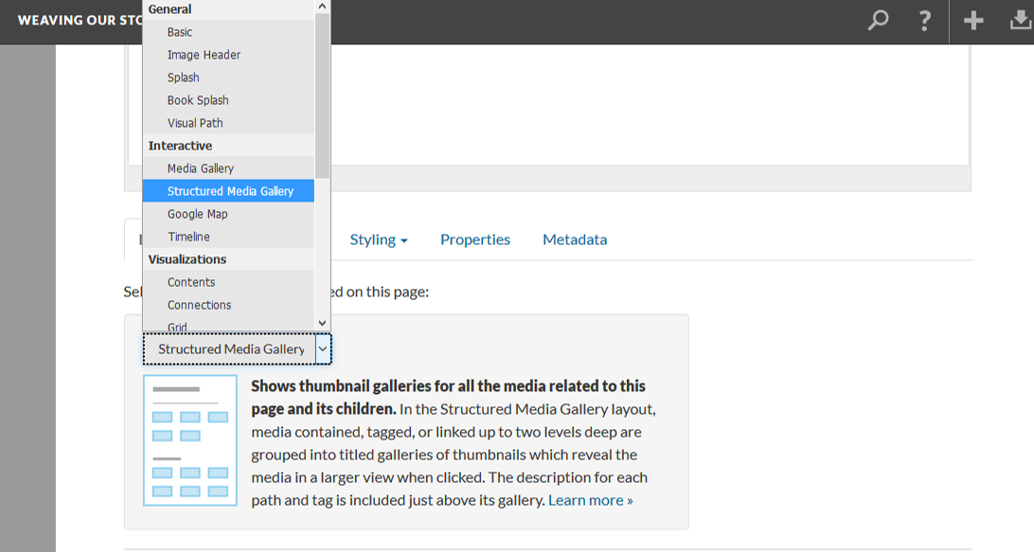

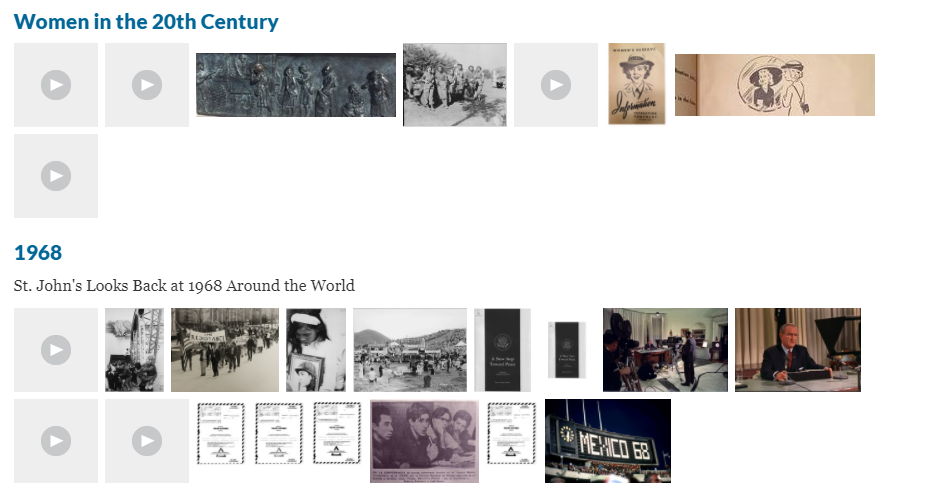

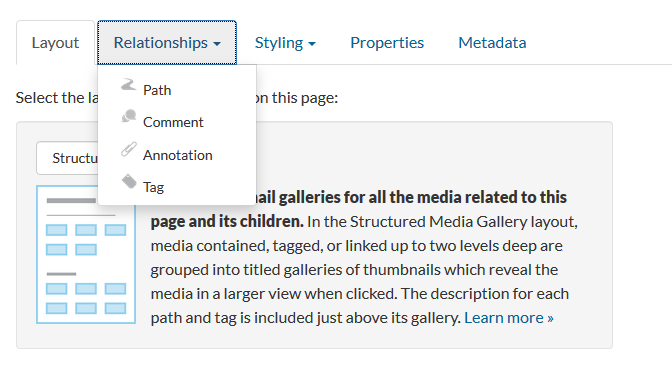

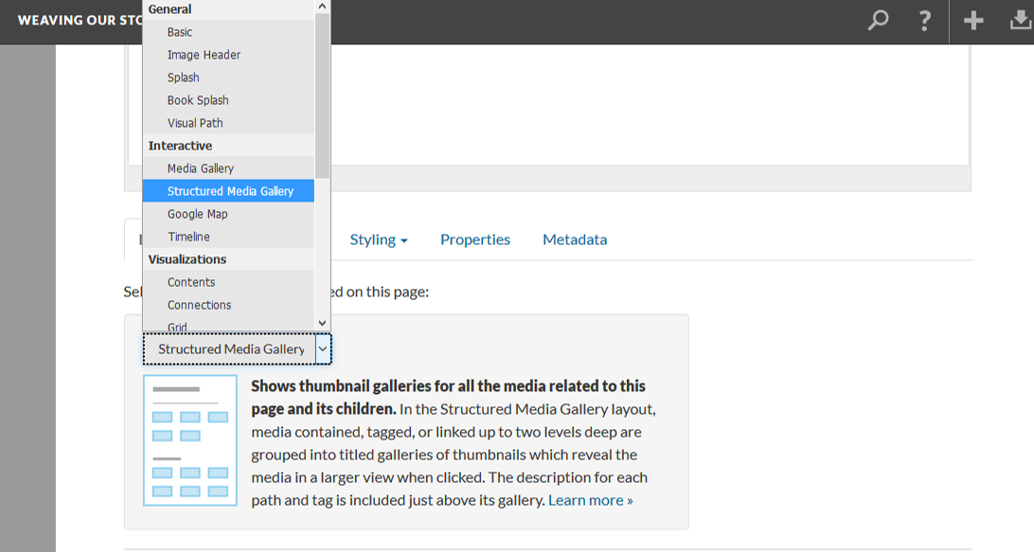

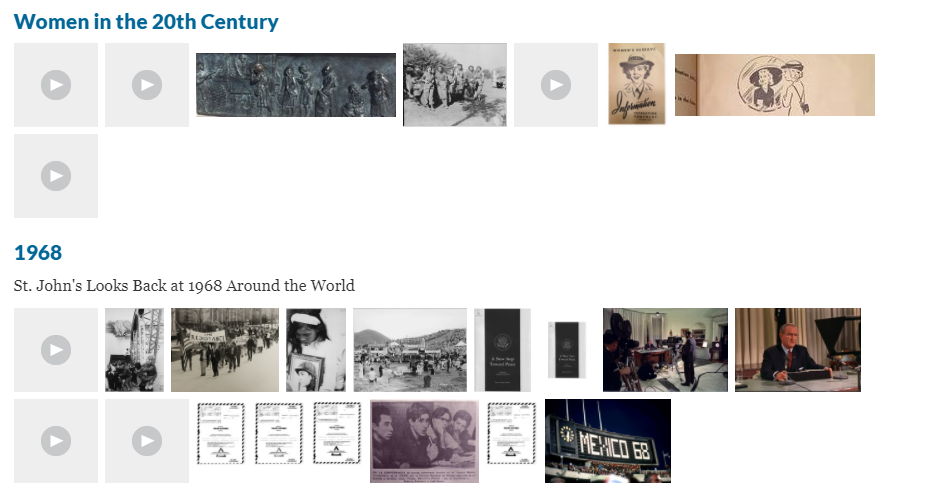

With these tags and paths in place, the author can create a new page that uses Scalar’s variety of layouts and visualization tools to draw upon these paths and tags. I have chosen to use Scalar’s Structured Media Gallery to create exhibit pages around certain “threads” in the Weaving Our Story archive such as 1968, the Vietnam War, and World War II. Scalar uses a “generous visual interface” by arranging thumbnails for each item in the exhibit on the main page. Users can explore the individual items in the exhibit and follow the “path” to the next item in the exhibit; however, each page is also tagged so that one could explore the connection between one item that is housed in two different exhibits. In this way, the reader is able to explore the complexities of histories presented and see the rich connections between and among the content.

Each exhibit page also exists as its own item and can become paths as well so that the exhibit pages appear on a separate launch page. Viewers can choose an exhibit path initially and then move along the exhibit path or explore connections.

I am excited by the possibilities Scalar offers me and how the Omeka site and the Scalar site work together. While Omeka can house the entire archive, the Scalar site is a more curated virtual museum exhibit. Not everything in a museum’s collection necessarily makes it into the exhibit.

The challenge to this is keeping up with the collection. I find myself wanting to add more and more outside resources to round out the exhibitions, but I realize that I may need to focus on the structure and format first. The global history of the 20th century is a vast topic to say the least, and I need to be realistic about what is possible by the end of the semester.

My goals for this week are to work on supplying textual content to the exhibits I’ve built. I also need to work on creating some content around the blog site for teachers by polishing some existing materials and creating new ones. I need to continue to work on permissions forms as well.