Argument, Design and Interpretation

The George W. Bush Presidential Center opened in 2013 on the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. The facility houses both the Bush Institute, a nonpartisan policy organization and the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum. The National Archives and Records Administration operates the George W. Bush Presidential Library.

Before entering the permanent exhibit, visitors view the multi-media film on the enormous LED screen in Freedom Hall. The visual symbolism of the display is meant to contextualize the role of the People in American democracy, a recurring theme throughout the museum. A key feature of this role involves decision making and many exhibits are interpreted to examine this process.

Freedom Hall Multimedia Display

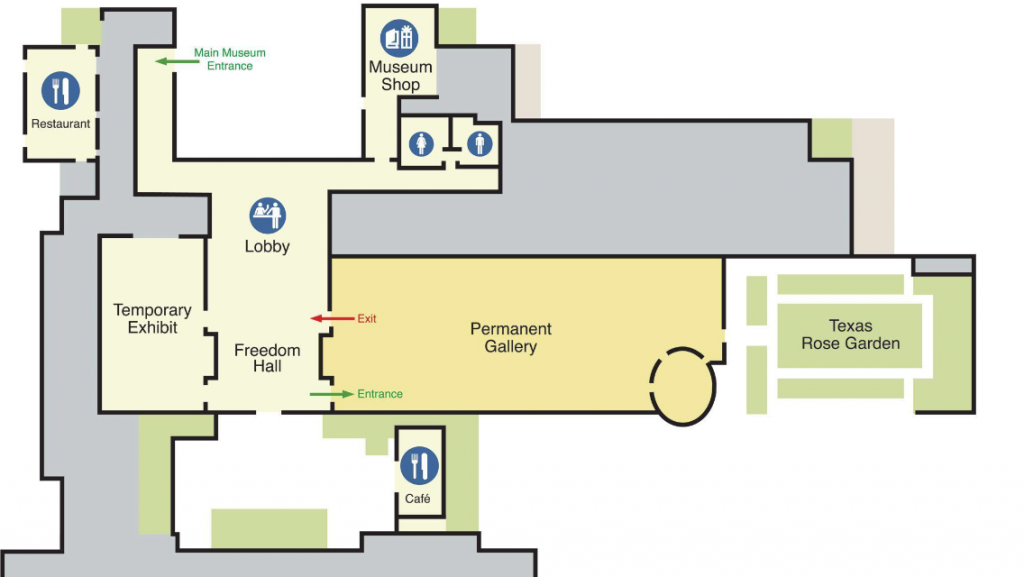

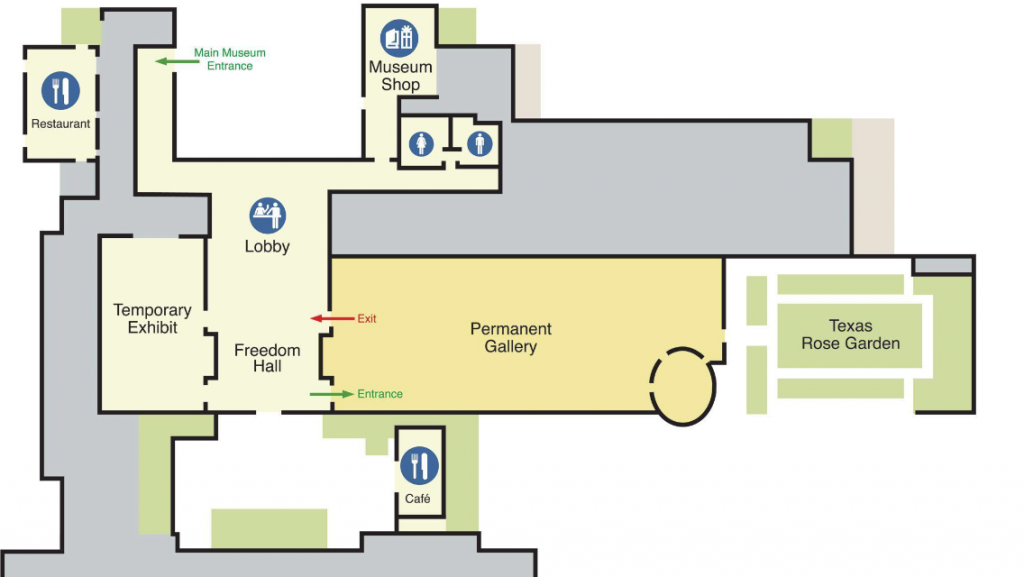

Site Layout, Navigation and Flow

The exhibit build out leads visitors through a generally chronological tour at the beginning of the exhibit. The Florida Recount, No Child Left Behind and other early policy initiatives precede the 9/11 exhibit which is in sharp contrast to what the visitor has previously experienced.

The exhibit build out leads visitors through a generally chronological tour at the beginning of the exhibit. The Florida Recount, No Child Left Behind and other early policy initiatives precede the 9/11 exhibit which is in sharp contrast to what the visitor has previously experienced.

This space is exceedingly well designed in that it presents the emotionally charged days surrounding 9/11 accurately and succinctly. The visitor can appreciate the blow by blow events of 9/11 itself and the national reaction in the immediate aftermath is recounted as well. The space is darker and takes advantage of the building’s tall ceilings to emphasize the twisted girder from the WTC central to the exhibit space.

As patrons proceed out of the 9/11 space, they are led around the corner to the left to explore other parts of the Bush presidency. However, a great failing of the exhibit design is that visitors often miss out on one of the most interesting spaces in the museum. So much so, that upon entering the exhibit, docents are trained to ask, “Have you been here before? Please don’t miss the Oval Office just past the 9/11 exhibit.” Other than directing traffic, docents did not generally engage with the public.

While visitors are drawn to the left, to the right is an exact replica of the Oval Office as it was furnished during the Bush presidency. The exhibit is not well marked in connection to the rest of the space. The necessity of having a window dictates where this exhibit lives within the larger layout of the museum so it wouldn’t be realistic to redesign where the exhibit is. However, greater care could be taken with signage or exhibit design that would more naturally draw people into the space. While the space is interesting and generates a photo-op, it does not deliver as a highly interpretive space. This area also leads visitors to some of the lighter moments of the Bush White House.

After the “detour through the White House,” patrons proceed through the rest of the exhibit where visitors learn about the President’s African Aids Initiative and the role of dissidents around the world. A large portion of this space is consumed by the Decision Points Theater. Comparable to the 9/11 exhibit in scope, this multi-media experience is central to the museum’s mission of developing decision making skills as part of civic engagement.

Finally, museum visitors are asked to consider the role the President and First Lady will play after leaving public life through service as citizen volunteers. Visitors are directed toward a kiosk where they can consider a variety of volunteer opportunities and are asked to “Be Citizens not Spectators.”

Audience and Accessibility

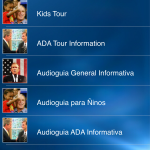

The space does make accommodations for visitors of a variety of ages as well as individuals and families. A seat behind the wheel of mini-school bus and a reading nook draw children into the No Child Left Behind exhibit. The Life in the White House video game offers opportunities for reflection and collaboration across generations. Obvious care had been taken to make displays, tags and interactives at a viewing level that are appropriate for the physically challenged, children and ambulatory adults alike. The majority of visitors seemed to be white and middle class and adult. The museum app provides a Spanish language digital tour for adults and children; however, all exhibit tags were in English.

Communication and Interpretation

The video screens in the 9/11 exhibit displayed looping news clips of the day’s major events and those immediately following. While the contextual elements were geared for adults, the video offerings provided an appropriate level of information for older children.

As a repository for the National Archives and Records Administration, the Bush Library and Museum seeks to further that mission by engaging adults in collecting 9/11 stories for preservation in the National Archives.

Video touch screens also helped visitors to analyze the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Like many exhibits in the Bush Library and Museum, the learning outcome is focused on the process of decision making rather than the outcome of the decision. Visitors commented on the “business school” aspects of the decision making process.

The Decision Points Theater is central to the museum’s argument about the importance of decision making in a democracy. The object is not only to teach the events themselves but also to help visitors undersand the difficulties of governing in a way that is forward looking. Throughout the museum, a good faith effort is made not to just to convince visitors WHAT to think but HOW to think about the decision making process as lifelong learners.

The exhibit dissects the thinking behind major crises of the Bush Presidency (Katrina, Iraq, Financial Crisis, etc.). Participants listen to pro/con arguments from a variety of sources in order to make a decision about how to take action. Responses are tallied among participants and majority rules. A video of President Bush explaining his reasoning on the actions undertaken by his administration follows to complement or contrast the decision of participants. Reviews have been mixed because of varying levels of perceived bias regarding the information presented. Adults having lived through those times also benefit from hindsight in evaluating the evidence presented.

Digital Media

GWB CENTER APP The Bush Center App is part of the museum’s digital presence though it has limited functionality away from the museum.

At the museum, the app contains differentiated tours for adults and children, including Spanish language versions of both. The Kid’s Tour falls decidedly flat, and the adult tour is bland as well.

The “My Gallery” section encourages visitors to record their museum visit though this requires that the app access the phone’s camera roll. It is unclear if this is only to connect to photos and videos taken at the museum or if it gives more general access. This lack of clarity could make some users uneasy.

Finally, the app allows visitors to participate in recording 9/11 stories as well. In the 9/11 exhibit there is one kiosk where visitors can do the same. Presumably, the app allows more visitors to access this capability while on museum grounds and without the pressure of “the next person in line” rushing such a personal experience. This is perhaps the most positive use of the app from a participatory standpoint.

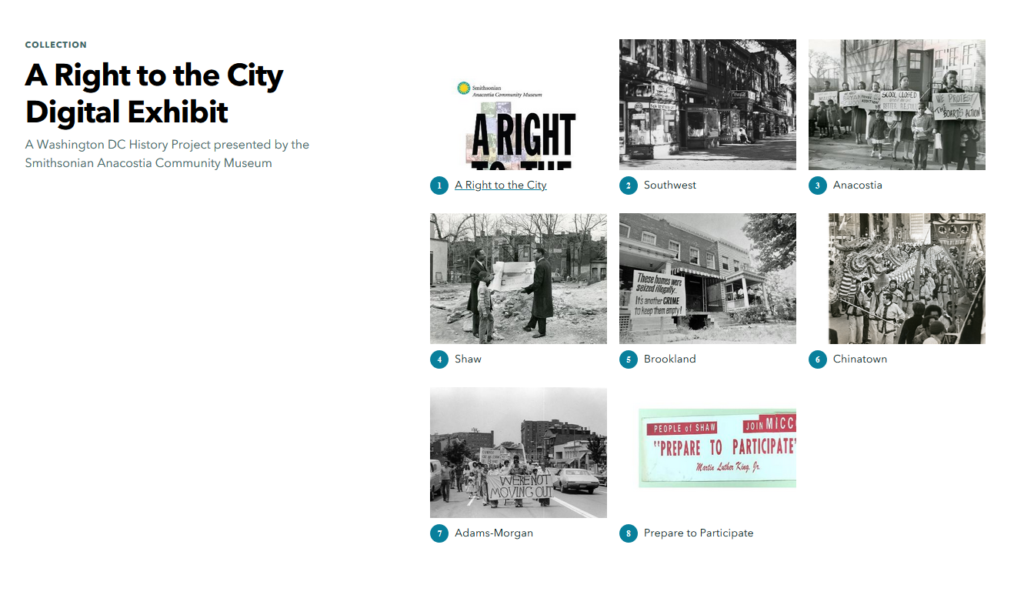

WEBSITE The George W. Bush Library and Museum website offers resources for planning a museum visit, links to upcoming events and digital publications as well as links about how to conduct research through the NARA. It also offers a collection of digital documents, photographs and films. The collection appears to be interesting, but the thumbnails are hard to navigate and do not include a point of reference in advance of looking at the image. Overall the website is good at delivering basic information, but it is a little unwieldy for someone interested in investigating the museum digitally. The design is generally geared for informational purposes only and does not give much thought to the historical arguments or interpretive choices in the museum itself.

The audience seems first to be potential museum visitors and afterwards researchers and students/educators. The landing page is generally well organized, though not all of the content is visible on the screen at one time. The site is fairly successful in conveying pertinent and helpful information about museum and research visits. However, because the site is linked to outside NARA resources as well as resources of the George W. Bush Presidential Center, the flow can be a bit unwieldy. The information for teachers and students is also unwieldy and gives off the feeling that the content was hurriedly created to “cross it off the list” in museum planning without any thought to overall strategy. One link in the “Kids’ Clubhouse” section takes young archivists to the same landing page for academic researchers. And, verbiage in a link to homework actually says “Fore more puzzles, games, trivia, and homework resources, try this website.”

The website is also heavily rooted in language. While images are included, the text is lengthy and often scroll over three or four screens. It is hard to know what is available because the sheer amount of verbiage is overwhelming.

Suggested Changes to the Digital Experience

THE GWB CENTER APP Great potential exists for a reboot of the app to make it much more engaging digital tool that would enhance the interpretive experience with a more interactive kids’ tour. A strong suit is the oral history gathering related to 9/11 and one wonders if that could be expanded to include other events of the Bush presidency such as Hurricane Katrina.

WEBSITE

OVERALL CHANGES The website is overly verbose and could do with a basic makeover to make it more streamlined and graphically appealing. The section on the museum itself could also be improved by connecting the arguments and interpretations in the physical museum to what is presented on the webpage. Educator resources such as the Traveling Trunk program focus on two very minor portions of the physical exhibit, and the Presidential Hats Program explains the activity but requires the educator to email for more information. It seems like this could be accomplished in providing a PDF of available resources at the very least. In both cases, the website could draw upon new tools, technologies and strategies to make these educational outreach programs more engaging.

THE SITUATION ROOM EXPERIENCE Apparently, the George W. Bush Library houses a portion of the former White House Situation Room Complex though it is not part of the general exhibit. Student groups are invited to role-play managing a constitutional crisis in these historic rooms though only 10 students may participate in the simulation at one time. Both the Bush Library and the Reagan Library run this 2017 MUSE Award winning Situation Room Experience.

The investment to make the resources supporting this visit available online is a sunk cost. To make the Situation Room Experience available to a larger audience on a practical level, both for those in proximity to these museums and for those who are not, the NARA should investigate the potentiality of making this a stand alone digital unit. While the point of the activity is to draw students into the museum, it is unlikely that this is a very broad draw from schools alone. And, the skills necessary to successfully navigate the simulation promote the goals of the physical museum in developing civic engagement and decision making skills in the PEOPLE of the United States.