DIGITAL CAPTURE

The practice of digital capture is central to work in digital humanities. However, implicit in the very definition of the word ‘capture’ is the idea of something being taken by force. While digital humanists aren’t out wielding weapons against librarians and museum curators, claiming digital preservation as a means of replacing collections, they are, in fact, forcing objects from one medium into another.

William Heath Robinson Inventions – Square Pegs into Round Holes From the Book: William Heath Robinson Invention, Public Domain

This is not a change from the material world into the immaterial – quite the contrary. Both mediums, analog and digital, have materiality, but the rules that govern each materiality differ. Thus, the process of digitization can inflict varying levels of trauma on the object being captured. In forcing a square peg into a round hole, some of the qualities of the object may be lost in order to make it fit. It is the job of digital humanists to fit as much as possible of the original into the digital circle and to attempt to preserve what is lost in translation as best they can using metadata and supporting information. Digital humanists must balance the costs associated with this remediation in considering what to digitize and by what method.

SENSORY ISSUES

Sensory information is often the largest category lost when an object or text is digitized. Obviously, the taste and smell of an object are almost impossible to capture. Digitization best captures material that can be imaged or recorded; however, even these capabilities are limited. Take for instance, sound recordings.

Once upon a time symphonies were only enjoyed by those who had financial access to assemble such a crowd of musicians. Today, metropolitan orchestras have democratized the musical experience for middle class masses, and digital recordings of symphonies are enjoyed by listeners in cars and homes alike. While it is possible to listen to the music, the experience of being part of the audience at one place in time cannot be duplicated.

Does the modern listener fully understand the performance in the absence of the atmosphere in which it was originally performed? Certainly not. Does an A/V recording of a contemporary symphony performance adequately capture the emotional response of the listener seated adjacent to the camera, or is it trained only on the performance? Is there something lost there? Yes. Despite these limitations, the recording clearly has value even though some of the richness of the experience is lost.

Nevertheless, sound recordings can be incredibly valuable as a tool for digital humanists. Creating digital repositories of dying dialects such as the Texas German Dialect Project preserve data for linguists and historians to study long after the language may have passed into oblivion. And, projects like StoryCorps offer opportunities for everyday people to add to the historical record.

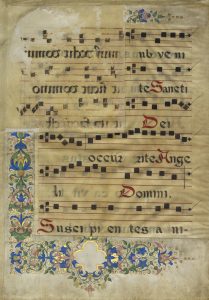

Francesco di Antonio del Chierico (Italian, 1433 – 1484) Music Text, third quarter of 15th century, Tempera and gold on parchment The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In a similar fashion, two dimensional images can capture a view of a three-dimensional object, but the material experience of the object will be incomplete. Visualization seems to work best for objects that are somewhat “flat” to begin with – think texts versus statues. Yet, even in the case of digitizing a page, the reverse side will always be left out. Items photographed in isolation lack scale, and weight and texture are difficult to assess. Video can help to solve these problems, but it still does not accurately capture the weight and texture of the item. Certainly, multiple angles, high-res images, proportional benchmarks or texts can help with these problems. Advances in imaging such as 360° views, panoramas and augmented reality may strengthen visual digitization as tool. However, these processes are cumbersome and can be expensive to produce, creating a volume of data that is expensive to maintain over the long term.

In many cases, visual digitization of objects can positively enhance how one interacts with an artifact. Details may be more readily seen because viewers can zoom in on a particular section. Archaic manuscripts that are not able to be handled physically for fear of degradation may be digitized and studied on a broader level. Individual pages from a volume of works may be read in a way that would be impossible if the volume were housed inside a glass case in a museum.

CHALLENGES

One challenge in working with textual digitization is the difference between an image of a text and text that has been processed through OCR (Optical Character Recognition) or rekeying (human visualization). Rekeying and OCR make visual copies of texts searchable by word. Rekeying is time consuming and can be cost prohibitive without using techniques such as crowdsourcing. Computer generated OCR is faster and less expensive in theory, but it is a classic example of a process when digital capture inflicts harm on its subject. Because the software is not perfect, even slight imperfections in character recognition can confuse meaning within a text. In reading texts such as recipes where precision is required, misreading ¼ as 4 will change the outcome entirely.

Like in traditional methods of preservation, funding and foot traffic remain important for keeping the collection relevant, whether it exists in analog or digital form. And, to a large extent, interest plays a huge role in what is collected. Some communities are more open to digitization either culturally or financially; therefore, the data available for study is largely dependent on the groundswell of support that exists for that data set.

OPPORTUNITIES

While digitization does not substitute for traditional methods of preservation, it does have its place within the humanities community. It can preserve a form of an object or text against total loss, and it can in some ways enhance the accessibility of objects and provide more detailed views than would ordinarily be available. Digital collections may be assembled virtually from collections across the globe.

Unknown Denarius, 1st century B.C., Silver 0.0039 kg (0.0086 lb.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Digitization has become a powerful force in places like the education community. As a secondary level history teacher, I have been able to bring a wide array of artifacts into the classroom. I am able to gather digital images of Roman coins to use in creating DBQ (Document Based Question) activities for my middle school students. Students can examine these rare coins and zoom in on details using their iPads thanks to the Open Content Program at the Getty Museum. Digitization makes it possible for them to work with content in ways that would have been impossible only ten years ago.

But, nothing will ever substitute for the ability observe the real thing, and in the case of my students, to actually hold a similar coin in your hand. The family of a former student graciously allows me to borrow his great-grandfather’s collection of Roman coins each year. Touching and, yes, even smelling it, students stare in wonder as they consider all the pockets and places the coin has traveled in its two millennia of existence. I am a lucky teacher to have access to both the analog and the digital versions of this ancient artifact. While the digital will never replace the real thing, it can enhance access to a broader group of people and enhance the ability to look carefully into the past.